The other day The US Airforce dropped a huge bomb on a set of tunnels in Afghanistan inhabited by IS jihadis, 36 of whom were reportedly killed. There were no civilian deaths. Publicly no one regretted the deaths, but many voices criticised the action as trigger-happy and unwisely threatening to the USA’s other enemies. Along with the destruction of a Syrian Airbase earlier last week, the bombing been widely interpreted as a warning to North Korea, which has replied by parading its own weapons and making suitably hysterical threats.

Most British commentary has focused on the incoherence of Trump’s foreign policy while Chinese voices have warned him to be much more cautious.

For myself, I considered the Syrian attack proportionate and perhaps effective as a deterrent, and the big bomb in Afghanistan as no more than a strategic initiative. The aggressors of this world require restraint, and their victims need support; the case for international police action is obvious in such situations. But that’s just the point: if actions like these are to be seen as just, that they must actually be international, that is, of the United Nations preferably, and if that is not possible, of a as large a coalition as can be obtained. The USA made only a token effort to get UN action against Assad, and none at all in the case of the Afghan attack, where they relied on a small existing coalition. In fact, in both instances, the USA seemed to pride itself on acting alone.

For myself, I considered the Syrian attack proportionate and perhaps effective as a deterrent, and the big bomb in Afghanistan as no more than a strategic initiative. The aggressors of this world require restraint, and their victims need support; the case for international police action is obvious in such situations. But that’s just the point: if actions like these are to be seen as just, that they must actually be international, that is, of the United Nations preferably, and if that is not possible, of a as large a coalition as can be obtained. The USA made only a token effort to get UN action against Assad, and none at all in the case of the Afghan attack, where they relied on a small existing coalition. In fact, in both instances, the USA seemed to pride itself on acting alone.

That cannot be right. Nobody has elected the USA as the world’s default policeman. When it acts as it has done this week it reinforces the suspicion that it believes it has the right to do as it pleases in any part of the world, by claiming that anything counter to its interest anywhere can be considered an attack on its territory, so that actions on the other side of the globe can be justified as “defensive.” None of this is new, and is certainly not an invention of President Trump. The much-admired President Obama held just as firmly to this policy of defending US borders at a distance. Indeed Mr Trump had promised a welcome departure from unilateral intervention by the USA.

Psalm 60 in the Christian bible confronts a situation in which nations surrounding Israel are crowing over a recent Israeli defeat. The psalmist imagines God rallying his people by reassuring them of his power over all nations. Of two of the nearest of these, God says, “Moab is my washpot and over Edom I have cast my shoe” using the picture of a traveller washing his feet by pouring water over them into a basin, after throwing his shoes into a corner. The nations of Moab and Edom are treated as negligible before the might of God.

The weapon used in Afghanistan this week was called MOAB, that is, Massive Ordnance Air Blast or more popularly, Mother Of All Bombs. It is the most powerful non-nuclear bomb ever used in war. Perhaps President Trump and his generals should listen to the book they frequently claim to cherish, and learn humility before the justice of God, which in secular terms means that humility is always wise, while arrogance is always stupid, sometimes terminally so. This MOAB is also God’s washpot.

Every now and again, something happens to wake me out the routine of religious duty in which by choice I live, to remind me that I have another life focused on words, on their meaning and beauty in the works of great writers of many languages, especially perhaps, in poetry. This is a life which I share with my wife who has an incomparable memory for such words, and with my late best friend, Bob Cummings, whose knowledge of the history of literature was the envy of other great scholars. To some of my readers this may seem a kind of life which is a bit precious and privileged, at some distance from the “real world.” But no, for me it has always helped my engagement with mundane reality that there is another dimension where words are neither banal nor ugly but come dancing with precision, rhythm, melody and meaning. If verbal langauge is one of the defining abilities of humanity, then surely its good use is one of our defining glories. Sometimes the great words may be profound like the opening of George Herbert’s poem:

Every now and again, something happens to wake me out the routine of religious duty in which by choice I live, to remind me that I have another life focused on words, on their meaning and beauty in the works of great writers of many languages, especially perhaps, in poetry. This is a life which I share with my wife who has an incomparable memory for such words, and with my late best friend, Bob Cummings, whose knowledge of the history of literature was the envy of other great scholars. To some of my readers this may seem a kind of life which is a bit precious and privileged, at some distance from the “real world.” But no, for me it has always helped my engagement with mundane reality that there is another dimension where words are neither banal nor ugly but come dancing with precision, rhythm, melody and meaning. If verbal langauge is one of the defining abilities of humanity, then surely its good use is one of our defining glories. Sometimes the great words may be profound like the opening of George Herbert’s poem:

You have heard that it was said by them of old times, ” You shall love your neigjbour and hate your enemy, but now I tell you: love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you, so that you may be children of your Father in heaven, for he causes his sun to rise on the bad as well as the good, and sends rain to fall on the just and the unjust alike.”

You have heard that it was said by them of old times, ” You shall love your neigjbour and hate your enemy, but now I tell you: love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you, so that you may be children of your Father in heaven, for he causes his sun to rise on the bad as well as the good, and sends rain to fall on the just and the unjust alike.” The suicide killer leaves his story to be told by others. In the case of the man who killed four people in London this week, and seriously injured many others, his story has already been appropriated by IS, with little justification, and will doubtless be pieced together by the British security agencies in time. We tend to think that acts of suicidal killing demand an explanatory story, as they are otherwise incomprehensible.

The suicide killer leaves his story to be told by others. In the case of the man who killed four people in London this week, and seriously injured many others, his story has already been appropriated by IS, with little justification, and will doubtless be pieced together by the British security agencies in time. We tend to think that acts of suicidal killing demand an explanatory story, as they are otherwise incomprehensible.

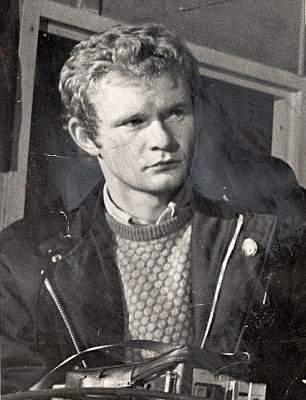

We may celebrate the conversion of a person from violence to such arts, as in the case of St Paul or the late Martin McGuinness, but we may guess that in both cases they were turned from violence as much by the quiet, enduring, courageous gentleness of some of their victims, as by the attractions of peace. The stories of such victims, along with that of Jesus, are the ones we need to tell, as publicly as possible. The human experiences which lead to violent impulses will always be present in people, but with the help of good stories rather than bad, they may sometimes be contained and used to fuel the struggle for justice and peace.

We may celebrate the conversion of a person from violence to such arts, as in the case of St Paul or the late Martin McGuinness, but we may guess that in both cases they were turned from violence as much by the quiet, enduring, courageous gentleness of some of their victims, as by the attractions of peace. The stories of such victims, along with that of Jesus, are the ones we need to tell, as publicly as possible. The human experiences which lead to violent impulses will always be present in people, but with the help of good stories rather than bad, they may sometimes be contained and used to fuel the struggle for justice and peace. One of the ways it’s not right is its racism, which is not at all peripheral to its message but central: God has chosen the Jewish people as his own, and therefore he treats other races as disposable. The promised land originally belonged to various other peoples, some semitic, some asian, some indo-european, who must have had their good points, but the Bible regards them as so much trash to be ethnically cleansed from Canaan so that God’s people can take it over. At times the Lord gets so annoyed at the continued survival of some of these tribes that he punishes his own people for not killing them off with sufficient thoroughness.

One of the ways it’s not right is its racism, which is not at all peripheral to its message but central: God has chosen the Jewish people as his own, and therefore he treats other races as disposable. The promised land originally belonged to various other peoples, some semitic, some asian, some indo-european, who must have had their good points, but the Bible regards them as so much trash to be ethnically cleansed from Canaan so that God’s people can take it over. At times the Lord gets so annoyed at the continued survival of some of these tribes that he punishes his own people for not killing them off with sufficient thoroughness. This would be so blatant an instance of racism, that I translate it as “Judeans” instead, which gives the author the benefit of the doubt, that he may be referring to Jews of a particular sect, rather than the whole race. On the face of it however, we have, right in the heart of Christian scripture, a gross prejudice which has been used down the centuries as an excuse for persecuting Jewish people. In one of the tragic turns of history a race whose ideology set it above all other races, became a race that could be persecuted by Christendom for the crime of deicide, the murder of God. Paul’s multi- ethnic community which welcomed all-comers became, and remained for much of history, a church in whose scheme of salvation the hatred of Jews was well-embedded.

This would be so blatant an instance of racism, that I translate it as “Judeans” instead, which gives the author the benefit of the doubt, that he may be referring to Jews of a particular sect, rather than the whole race. On the face of it however, we have, right in the heart of Christian scripture, a gross prejudice which has been used down the centuries as an excuse for persecuting Jewish people. In one of the tragic turns of history a race whose ideology set it above all other races, became a race that could be persecuted by Christendom for the crime of deicide, the murder of God. Paul’s multi- ethnic community which welcomed all-comers became, and remained for much of history, a church in whose scheme of salvation the hatred of Jews was well-embedded. The contamination of the Bible by racism is evidence that there is a deep-seated human impulse to fear the stranger, which can be corrupted into arrogance, exclusivity and hatred. If followers of Jesus are to oppose racism in their own societies and beyond, they must begin by confessing the racism in their holy book. But more, they should study the evidence of inclusiveness, multiracialism and equality in the writing of St Paul and in the communities of Jesus Messiah which he established. By any standards the man who argued that in his Messiah there was neither Jew nor Gentile, neither male nor female, slave nor free, deserves attention at a time when varieties of populism succeed by blaming the woes caused by capitalism on people of other race or nationality. If Christian churches could translate Paul’s inclusiveness into contemporary words and actions, they could redeem their own traditions and help build a humane alternative to the aggressive ghettos of Wilders, Farage, Trump and their like.

The contamination of the Bible by racism is evidence that there is a deep-seated human impulse to fear the stranger, which can be corrupted into arrogance, exclusivity and hatred. If followers of Jesus are to oppose racism in their own societies and beyond, they must begin by confessing the racism in their holy book. But more, they should study the evidence of inclusiveness, multiracialism and equality in the writing of St Paul and in the communities of Jesus Messiah which he established. By any standards the man who argued that in his Messiah there was neither Jew nor Gentile, neither male nor female, slave nor free, deserves attention at a time when varieties of populism succeed by blaming the woes caused by capitalism on people of other race or nationality. If Christian churches could translate Paul’s inclusiveness into contemporary words and actions, they could redeem their own traditions and help build a humane alternative to the aggressive ghettos of Wilders, Farage, Trump and their like.

It was reading Confucius that made me think of it.

It was reading Confucius that made me think of it.

Confucius is one of my favourite philosphers, not least because he taught that the virtue of shu, reciprocity, should be very strictly practiced by younger people in their treatment of older people, like me.

Confucius is one of my favourite philosphers, not least because he taught that the virtue of shu, reciprocity, should be very strictly practiced by younger people in their treatment of older people, like me.