We all know that nothing lasts.

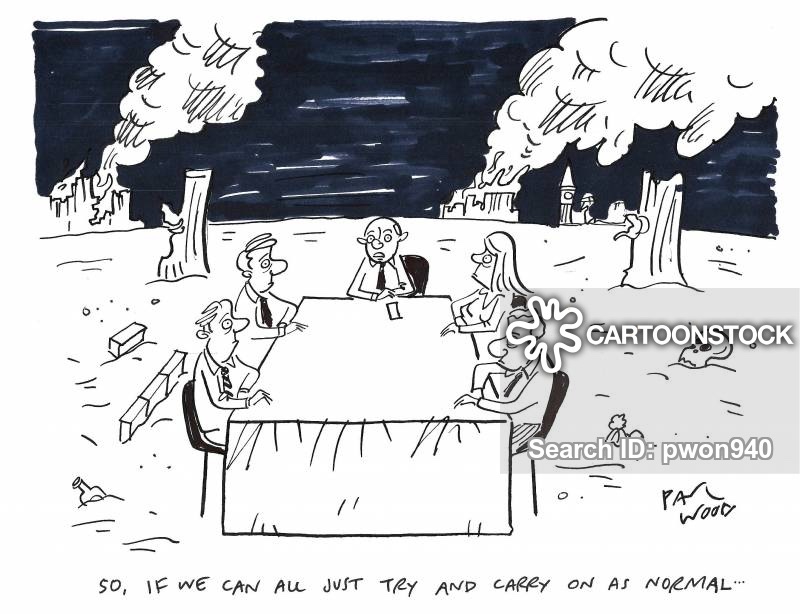

From the motor car that we hoped would see us through another year to the old friend we’d meaning to see once again, we can find our expectations dashed by the ability of things to wear out or to be smashed by accident. We know this, yet we are shocked and grieved when it involves something or someone dear to us; and in spite of the ravages of time on the face and alcohol on the liver, we refuse to accept that it happens to us: no, no, amidst the ruins we, our fundamental selves, are the same. Aye right! The bright certainties of my youth, that I was wonderful and the world my oyster, where have they gone? They and the person that believed them have not lasted.

I went walking in the hills yesterday, continuing a project that I began with my late daughter, to climb all the hills between 2000 and 3000 feet in the county of Angus, in which I live. It was conceived partly out of a recognition that she might no longer be fit for the higher hills, but could rebuild her health on these smaller ones. It was not to be. On the hill, however, enchanted again by beauty and solitude, I felt comfortably close to her, remembering particularly her knowledge of landscape forms and their history. She would have understood how these hills were once of alpine height at least, thrust into the air by the force of clashing tectonic plates, only to be ground down by wind and rain until they were sculpted anew by the glaciers that munched through them in the ice ages. She would have been able to tell me where the local ice cap was located and the direction of the glacier flow.

At the top we would have shared together some bars of caramel shortbread, which we had long considered the ideal mountain snack, ever since we discovered a garage where the youthful attendant sold his granny’s version of it under the counter. Now both the granny and the garage are gone. Then we would have argued furiously about whether that was Lochnagar – non-Scottish readers need told that this is a mountain- rising in the middle distance. As I stood alone on the summit of the Hill of Sauchs, I imagined that it was lower by some tiny but measurable amount as a result of erosion, than when I visited this glen as a teenager more than sixty years ago.

Doubtless these thoughts of mutability were due to my daughter’s recent death. I remembered some lines by one of my favourite poets, “The hills are shadows and they flow/ from form to form and nothing stands.” Today I looked up the passage, from In Memoriam, section 23/24,, recollecting that Alfred Tennyson wrote the poem following the death of his dear friend, Arthur Hallam:

There rolls the deep where grew the tree.

O earth, what changes hast thou seen!

There where the long street roars, hath been

The stillness of the central sea.

The hills are shadows, and they flow

From form to form, and nothing stands;

They melt like mist, the solid lands,

Like clouds they shape themselves and go.

But in my spirit will I dwell,

And dream my dream, and hold it true;

For tho’ my lips may breathe adieu,

I cannot think the thing farewell.

(The “thing” is of course his friend)

His friend, at least in his human form, has not lasted, but his friendship endures, across the gap of death. This fact leads him to think directly of human faith in something or someone that might transcend the realm of life-and-death

CXXIV.

That which we dare invoke to bless;

Our dearest faith; our ghastliest doubt;

He, They, One, All; within, without;

The Power in darkness whom we guess;

I found Him not in world or sun,

Or eagle’s wing, or insect’s eye;

Nor thro’ the questions men may try,

The petty cobwebs we have spun:

If e’er when faith had fall’n asleep,

I heard a voice ‘believe no more’

And heard an ever-breaking shore

That tumbled in the Godless deep;

A warmth within the breast would melt

The freezing reason’s colder part,

And like a man in wrath the heart

Stood up and answer’d ‘I have felt.’

No, like a child in doubt and fear:

But that blind clamour made me wise;

Then was I as a child that cries,

But, crying, knows his father near;

And what I am beheld again

What is, and no man understands;

And out of darkness came the hands

That reach thro’ nature, moulding men.

This is an astonishing section. The first stanza makes clear that the “God” he imagines is not the well-defined God of Christian theology. His list of the arguments which have not led to his enlightenment includes cosmological arguments and arguments from design, which then as now focused on the eye as an organ which ‘must have been’ designed as a whole. None of them cuts the mustard for him. His discovery comes from the most painful experience of doubt, without which he would have remained in reasoning alone. We should note that the great stanza which ends “I have felt” does not mean “I have felt there is a God, and that outweighs the experience of doubt” but rather “I am a creature that feels and has felt, especially the love I have felt for my friend.” This love is his identity which, he asserts, is just as real as the changing earth. He does not deny the facts of change and death, but makes them part of what he feels, which prompts his cry to the one who is near to the crying child.

All logic and common sense tells us that Tennyson should have called this presence “mother” as of course it’s the mother who is near to the crying child while the father is in the library writing poetry

“ And what I am beheld again/ what is” He asserts his true identity as a being that feels, because only as such can he feel the “hands that come out of darkness” the darkness of change, death and sorrow, moulding him in and through these natural experiences.

These sections are the turning point of the poem, and are also helpful to me. They tell me that I must not deny the truth that nothing in this world lasts, but that there is a greater wisdom in my sorrow than in my reasoning, because the facts of human love and rage at its interruption, may be the only things that point to something that outlasts the hills.

The great Buddhist teacher, Dogen, in his collection of meditations called Shobogenzo, sums up a reflection with the words:

“You, who are learning to be Buddhas, who are practicing the Way in this age, open your minds to the mountains that flow and the rivers that do not.”

Or, as Isaiah put it:

“For the mountains shall depart and the hills be removed; but my lovingkindness shall not depart from you, says the Lord that has mercy upon you.”