The most thought-provoking words I read during Holy Week was the Good Friday headline of the Scottish Daily Record:

WOMAN SAVES TARANTULA FROM CHILDREN

The accompanying text told how a woman in Bellshill near Glasgow had stopped some children from hurting a tarantula which had escaped from a nearby house. The RSPCA took charge of the animal which they declared to be in a robust condition. In the whole report there was not a word to suggest that this sequence of events was not entirely normal. It was flanked by a story about how a Scottish woman had trained her parrot to use the loo. “For this is my country….”

The beauty of the story is that it correctly identifies children as more dangerous than tarantulas, because of course Homo Sapiens is the most deadly of all predators, daily responsible for more kill than Tyranosaurus Rex managed throughout his history.

I have been taken to task by a number of readers for my pessimistic blog which doubted if the human race would survive its own evil and folly. In particular a number of Christian believers asked how such pessimism could be reconciled with faith in the God of Jesus. After all, we are told to pray “Thy kingdom come” which surely cannot mean that humanity will be wiped out by global warming. We are commanded to take no thought for tomorrow, which surely suggests that gloomy prognoses such as mine are contrary to the spirit of Jesus. And doesn’t God guarantee in the Noah story that seed time and harvest will never cease again?

The biblical realism of the Afro- American slaves knew better:

God gave Noah the rainbow sign

No mo’ water but the fire next time.

That Spiritual picks up the plain truth of the witness of the New Testament with regard to the future of the earth: it won’t end well. Yes, God will rescue his faithful people, who have not contaminated themselves with power or wealth or other idols, but have trusted in the way of Jesus, these God will rescue from the destruction which will come upon the world. This type of theology is called eschatological (meaning thought about the end-times) or apocalyptic (meaning a revelation of God’s hidden purpose), and there’s a lot of it in the New Testament, more than can simply be ignored as an aberration. Almost all books of the New Testament contain some reference to the short future of the world. Of the Gospels only John fails to report the eschatological prophecy of Jesus. Most of the Pauline letters mention the shortness of the time of God’s patience and look towards the final appearance (Greek, Parousia) of Jesus Messiah; and the book of The Revelation contains nothing other than visions of the approaching end of this world, and the arrival of new heavens and a new earth. The end always involves God’s judgement on the powers of evil and their adherents and the reward of those who have remained true to Jesus.

There are all kids of subtle differences in way different writers use this kind of material, but there are a number of common convictions:

- While the death of Jesus on the cross reveals the astonishing goodness of God; it also reveals the astonishing evil of humanity.

- Jesus’ death on the cross is depicted as an eschatological event: the sun refuses to shine and the dead rise from their graves. The New Testament writers assume therefore that the end times have arrived. Other eschatological events may not be immediate but they are imminent.

- In the remaining time of God ‘s patience the Gospel of God’s Rule in Jesus has to be announced world-wide so that before the end people from all races may turn towards the God who will rescue them from the day of wrath.

- The establishment of God’s Rule on earth will not be a continuation of this world. If McCoy happened into it, he would say accurately, “It’s life, Jim, but not as we know it.”

In time, the texts which more or less clearly pointed to the swift return of Jesus and the ending of the world as we know it, became an embarrassment to the church and were interpreted as pointing to a remote future or spiritualised as symbols of the judgement that comes upon people at death. Many churches, recognising that those who are fascinated by this material are usually nutters, such as the 1984 people who awaited the end on top of Mont Blanc and hadn’t enough money to pay their hotel bills when they finally descended, or the pathetically deranged creatures who expect some variety of rapture, steer clear of the whole topic.

But like the homophobes say of homophobia, “it’s there in scripture,” and in this case it’s not in a few stray references, like homophobia, but is a central element in the witness of the New Testament.

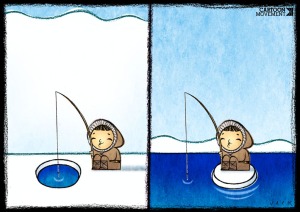

I love this earth and would like to be optimistic about its future. In fact, given what I know scientifically about life, I am reasonably optimistic about the future of the physical planet and life on it, and would like to extend this optimism to include the human race, but cannot do so with any conviction. Homo sapiens may turn out to have been an evolutionary cul de sac. That rational doubt about the long term future of human beings is supported rather than rebutted by the theological witness of the Bible. The great flood of the bible story is God’s exasperated response to the evil caused by the creatures made in his likeness. God ends up sorry that he destroyed so much of his original creation but there’s nothing in the story about human sorrow for their evil. Sure enough, scarcely has God unveiled the rainbow than Noah’s drunk and causing trouble. God’s decision to persevere with humankind looks like the triumph of hope over experience.

Pessimism need not weaken faith, nor the commitment of believers to oppose human arrogance, violence and stupidity while there is the least chance of averting disaster. Optimism on the other hand may lead people to ignore the ominous signs of what our grandchildren may face in their lifetimes.

That phrase of Shakespeare’s has been in mind for a few days as an accurate description of what I see when I look at the activity of the human race. We face an increasing threat of devastating global warming, which has already begun to affect many countries and will soon affect all, and the response of the rich and powerful of the world is to try to run things so that they will become richer and more powerful even if they end up in artificial environments poised on the surface of a burnt out planet. This means conspicuous consumption of earth’s diminishing resources, complete carelessness with the lives of the poor and the creatures or the earth, and vicious brutality towards anyone who gets in the road. And the Islamic jihadis who claim to stand for justice in opposition to the power of the rich, are touched by a hysterical self-righteous extremism that simply adds to the evils they try to oppose.

That phrase of Shakespeare’s has been in mind for a few days as an accurate description of what I see when I look at the activity of the human race. We face an increasing threat of devastating global warming, which has already begun to affect many countries and will soon affect all, and the response of the rich and powerful of the world is to try to run things so that they will become richer and more powerful even if they end up in artificial environments poised on the surface of a burnt out planet. This means conspicuous consumption of earth’s diminishing resources, complete carelessness with the lives of the poor and the creatures or the earth, and vicious brutality towards anyone who gets in the road. And the Islamic jihadis who claim to stand for justice in opposition to the power of the rich, are touched by a hysterical self-righteous extremism that simply adds to the evils they try to oppose.

Come on, come on, someone will be saying, all this is some kind of provocation, you don’t really think this. Ah but I do, and one of the strongest supports for my argument is myself: why haven’t I fought harder? Why have I sometimes added my own evil and destructiveness to the common pile? My only excuse is that I’m a human being.

Come on, come on, someone will be saying, all this is some kind of provocation, you don’t really think this. Ah but I do, and one of the strongest supports for my argument is myself: why haven’t I fought harder? Why have I sometimes added my own evil and destructiveness to the common pile? My only excuse is that I’m a human being.

The cross is not the grim story of a psychopathic God who demands satisfaction from his Son, but the sober story of the Son of God who poured out the Father’s generosity in life and death, the victim of moralism, meanness, prejudice, hatred and fear, yet still undefeated. Jesus faithfulness unto death to the generosity of God, is as St Paul recognised, the end of all religious systems designed, like the Torah, to secure the blessing of God. As Jesus knew, the blessing is already given to those who turn to God, in spite of their sins. Now, in that blessing, they have to start again, and again and again.

The cross is not the grim story of a psychopathic God who demands satisfaction from his Son, but the sober story of the Son of God who poured out the Father’s generosity in life and death, the victim of moralism, meanness, prejudice, hatred and fear, yet still undefeated. Jesus faithfulness unto death to the generosity of God, is as St Paul recognised, the end of all religious systems designed, like the Torah, to secure the blessing of God. As Jesus knew, the blessing is already given to those who turn to God, in spite of their sins. Now, in that blessing, they have to start again, and again and again. Writing blogs about matters of faith may create an image in the mind of readers of someone constantly taken up with the great teachings of Christianity, while leading a life of disciplined piety and virtue.

Writing blogs about matters of faith may create an image in the mind of readers of someone constantly taken up with the great teachings of Christianity, while leading a life of disciplined piety and virtue.

Giles Fraser is a priest of the Church of England with an honourable record of putting his own interests at risk for the sake of justice. He writes a weekly column in the Guardian newspaper in which he reflects on political and social issues from a religious perspective. Today his article is a denunciation of Donald Trump, who is certainly a deserving target; but the arguments used in the article are lazy, trite and prejudiced about American Christianity in particular, and Americans in general.

Giles Fraser is a priest of the Church of England with an honourable record of putting his own interests at risk for the sake of justice. He writes a weekly column in the Guardian newspaper in which he reflects on political and social issues from a religious perspective. Today his article is a denunciation of Donald Trump, who is certainly a deserving target; but the arguments used in the article are lazy, trite and prejudiced about American Christianity in particular, and Americans in general.

George Clooney, speaking as a concerned fellow citizen has called Donald Trump a fascist. This may not bother someone who knows as little history as Trump, but it invites Americans to look at the the policies Trump has articulated and to compare them with those of, for example, Mussolini. That’s unfriendly but fair, because it can be examined and found to be true or false. It is part of a debate between fellow citizens.

George Clooney, speaking as a concerned fellow citizen has called Donald Trump a fascist. This may not bother someone who knows as little history as Trump, but it invites Americans to look at the the policies Trump has articulated and to compare them with those of, for example, Mussolini. That’s unfriendly but fair, because it can be examined and found to be true or false. It is part of a debate between fellow citizens.