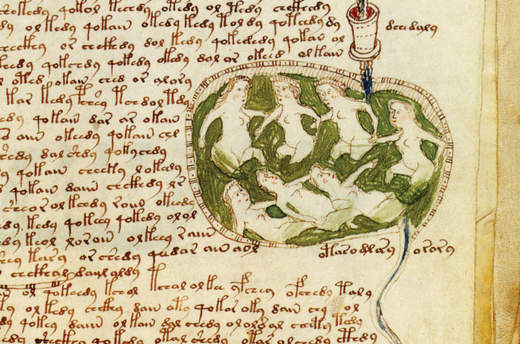

Over the years I have occasionally come across mention of the VOYNICH MANUSCRIPT, which has just been published by Yale at 35$. It has been dated to the 15th century and is a vellum scroll containing what appear to be words, written in an unknown but elegant script, together with illustrations that are recognisable, as plants, insects, geometrical shapes, buildings and most famously, naked women bathing together. The text has been as scientifically analysed as possible and is said to possess many of the characteristics of written language, for example in respect of the frequency of recurrence of certain word-forms. The manuscript has been intensively, almost compulsively studied by cryptologists, linguists, mathematicians and specialists in forms of magic/ religion/ philosophy and hocus-pocus, all without result. Its earliest known possessor declared it to be the work of the medieval magus, Roger Bacon, but of this there is no other evidence.

I confess to finding its mystery interesting, and have even taken a look at it – you can find a pdf version online- in the vague hope that I might instantly recognise the language as one of my childhood linguistic codes of speaking backwards or infiltrating ordinary words with those of “All things bright and beautiful” used in strict order. This discovery would a) reveal the eminent scholars as idiots and b) me as a genius. Sadly this is not the case. Those who look at it however, will not easily forget it, because it appears so friendly, so to speak, so open to interpretation, so encouraging to the reader, while remaining utterly incomprehensible, like the humanoid child who emerges from the alien spaceship smiling affably and speaking a language which remains utterly beyond interpretation.

I have sometimes suspected that my liking for this mystery sheds a dubious light on my liking for the Bible, which some have seen as an utterance of God that defies human minds, unless one possesses the key to its interpretation. Can it be that my persistent and obsessive attempts to decode the scriptures arise from a conviction that no wholly persuasive interpretation has ever been made? That the Bible is an even more alluring mystery than the Voynich MS because it pretends to be accessible, written in human languages that can be translated, while being cunningly designed to baffle us? No, I don’t think so, because I see the Bible as a collection of great literature, which like all great literature demands to be interpreted and re-interpreted by every generation and ultimately by every reader, so that every honest reading adds something valuable to its meanings. Of course, there is no final interpretation of the Bible any more than there is a final intepretation of King Lear or The Magic Flute. They avoid finality because they are alive.

No, it’s not my interpretation of the Bible that reminds me of the Voynich MS. But I remain convinced that its incomprehensibility is linked to something more fundamental in my life. And that phrase turns out to be my clue. Yes, it’s my life, the fundamental fact of my life in this universe, that’s like the Voynich MS. It’s as if the events of my life, all of them, the people who have shared them, the space/time in which they have happened and all the multitudinous existences of which I have been aware, all of it, although my culture tells me I can understand it, is written in a script composed of galaxies and particles, in a language of universal energy, expressing a truth which is forever beyond me.

And yet, like the manuscript, it seems friendly, inviting my engagement with it, my cooperation in creating new interpretations, my appreciation of its endless wonders, my love for all the other characters in its unending story. Some will feel that I am exaggerating human ignorance but when I listen to Brian Cox telling us that our best cosmology accounts for maybe 5% of universal matter, or when I ask how my wife has been good to me for 50 years, I am sure of at least my ignorance, as I walk (happily) in worlds I do not know.

Yes, it’s better than Dan Brown.

These words show a loving heart that will arouse affection for their speaker in all who read them over the years, and scorn for the regime which has silenecd him.

These words show a loving heart that will arouse affection for their speaker in all who read them over the years, and scorn for the regime which has silenecd him.

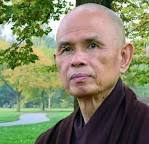

Buddhism is a profound revelation of wisdom, but it has become the ideal religion for busy capitalists, who benefit from its mindfulness training and meditation while neglecting its teachings on compassion. Its denial of a “real self” fits well with capitalism’s denial of meaningful life to both its devotees and its victims. Thich Nhat Hanh has throughout his pilgrimage shown his own commitment to the fruitful life of all creatures, including the victims of war and oppression. I think there is an issue to do with the intersection of fact and faith, history and mystery, which demands his further consideration.

Buddhism is a profound revelation of wisdom, but it has become the ideal religion for busy capitalists, who benefit from its mindfulness training and meditation while neglecting its teachings on compassion. Its denial of a “real self” fits well with capitalism’s denial of meaningful life to both its devotees and its victims. Thich Nhat Hanh has throughout his pilgrimage shown his own commitment to the fruitful life of all creatures, including the victims of war and oppression. I think there is an issue to do with the intersection of fact and faith, history and mystery, which demands his further consideration.

Is this still the case today or should we admit that there has never been a city whose benefits outweighed its appalling injustice and that there never will be; that even God cannot bring together hundreds of thousands or millions of human beings without also bringing injustice and squalor. Should we admit that the human dream expressed in the creation of cities is a busted flush, an idol that has presided over oppression and bloodshed for 10,000 years, which cannot be cleansed even by the blood of the Lamb?

Is this still the case today or should we admit that there has never been a city whose benefits outweighed its appalling injustice and that there never will be; that even God cannot bring together hundreds of thousands or millions of human beings without also bringing injustice and squalor. Should we admit that the human dream expressed in the creation of cities is a busted flush, an idol that has presided over oppression and bloodshed for 10,000 years, which cannot be cleansed even by the blood of the Lamb? Psalm 139World English Bible (WEB)

Psalm 139World English Bible (WEB)

“I am fearfully and wonderfully made…..”

“I am fearfully and wonderfully made…..”

I’ve been reading. Yanis Varoufakis, eapecially his recent books, “And the weak suffer what they must?” and “Adults in the Room” with pleasure, and some amazement at his ability to make complex economic matters clear to this ageing brain. These are books which challenge to the prevailing ethos that we are here to consume and must struggle to get a decent share of scarce commodities. Of course everyone would like to consume lots, but because our banks went mad, we all have to be very restrained and put up with austerity, all of us that is, except the bankers and other rich people who contributed to the madness. Varoufakis thinks that the planet is very rich and that if its resources are used intelligently there’s more than enough for everybody. What’s more, the true richness of life does not consist in consumption, but in sociability, adventure, knowledge, healing and creativity. The sense of scarcity and the insistence on consumption, he says, benefit those who already hold wealth and power but still want to consume more. He does not think that the purveyors of austerity are wicked, but that their love of power and its rewards has blinded them to any fact that might disturb their illusion.

I’ve been reading. Yanis Varoufakis, eapecially his recent books, “And the weak suffer what they must?” and “Adults in the Room” with pleasure, and some amazement at his ability to make complex economic matters clear to this ageing brain. These are books which challenge to the prevailing ethos that we are here to consume and must struggle to get a decent share of scarce commodities. Of course everyone would like to consume lots, but because our banks went mad, we all have to be very restrained and put up with austerity, all of us that is, except the bankers and other rich people who contributed to the madness. Varoufakis thinks that the planet is very rich and that if its resources are used intelligently there’s more than enough for everybody. What’s more, the true richness of life does not consist in consumption, but in sociability, adventure, knowledge, healing and creativity. The sense of scarcity and the insistence on consumption, he says, benefit those who already hold wealth and power but still want to consume more. He does not think that the purveyors of austerity are wicked, but that their love of power and its rewards has blinded them to any fact that might disturb their illusion.

I am grateful to Varoufakis for his searching analysis of European economic problems, and even more, for his vision of plenty, which, he might be surprised to find, has deep roots in the biblical tradition.

I am grateful to Varoufakis for his searching analysis of European economic problems, and even more, for his vision of plenty, which, he might be surprised to find, has deep roots in the biblical tradition.