That phrase of Shakespeare’s has been in mind for a few days as an accurate description of what I see when I look at the activity of the human race. We face an increasing threat of devastating global warming, which has already begun to affect many countries and will soon affect all, and the response of the rich and powerful of the world is to try to run things so that they will become richer and more powerful even if they end up in artificial environments poised on the surface of a burnt out planet. This means conspicuous consumption of earth’s diminishing resources, complete carelessness with the lives of the poor and the creatures or the earth, and vicious brutality towards anyone who gets in the road. And the Islamic jihadis who claim to stand for justice in opposition to the power of the rich, are touched by a hysterical self-righteous extremism that simply adds to the evils they try to oppose.

That phrase of Shakespeare’s has been in mind for a few days as an accurate description of what I see when I look at the activity of the human race. We face an increasing threat of devastating global warming, which has already begun to affect many countries and will soon affect all, and the response of the rich and powerful of the world is to try to run things so that they will become richer and more powerful even if they end up in artificial environments poised on the surface of a burnt out planet. This means conspicuous consumption of earth’s diminishing resources, complete carelessness with the lives of the poor and the creatures or the earth, and vicious brutality towards anyone who gets in the road. And the Islamic jihadis who claim to stand for justice in opposition to the power of the rich, are touched by a hysterical self-righteous extremism that simply adds to the evils they try to oppose.

There is nowhere on earth that offers me news of anything better; the many people who work for justice, goodness and beauty are forced to exist on the margins of power and are always vulnerable to its priorities.

Yes, I know this sounds extreme, but my view stems from the realisation that I have been wilfully optimistic in refusing to see that the destructive people are more powerful that the others, and that most of what actually happens is what they want to happen. How could I have failed to see this? I think probably I didn’t want to see it and therefore ignored it. Check it with your own view of the world- that’s the reality, isn’t it? – it’s going to hell in a handcart, because we’ve permitted comfy rich boys, like the U.K Chancellor of the Exchequer, who is presently delivering a budget which will enhance the lives of the rich and damage those of the poor, while failing to address any of the real problems of our country, to decide our futures. Yes, yes, it’s called democracy, I know. But does anyone think that their grandchildren, who are already poorer than them and will live precarious lives on an overheating earth, subject to vicious wars for the remaining sources of energy, does anyone think they’ll be grateful that it was all done democratically?

The instinct of people who begin to see how they’ve been shafted is not encouraging: witness the rise of right wing parties in Europe, the US, and in many other places. They have a common gift to their supporters: someone to blame other than themselves, for the state of the world, usually foreigners. Clearly these people are not seeking real solutions. They want instant magical solutions that will solve the problem at a stroke, building walls over vast territories to keep foreigners out (Trump) or jailing everyone who disagrees (Putin). None of these are quite as mad as North Korea’s drive to make its armed forces larger than its civilian population, but they’re at least competing. Nothing rational has any effect on the pathetic, demented, squealing rage that falls for these solutions. It’s as if the passengers on the Titanic, being warned that it might crash, started fighting to finish the whisky and diverted the crew’s attention from the danger.

I used to quote Gramsci, the great Italian Marxist, who prescribed, “pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will,” meaning that things would probably go wrong but you could fight them successfully. I still want to fight and will continue in this blog to encourage others to fight, but I don’t anticipate victory: I think evil and destruction are the default settings of the human race.

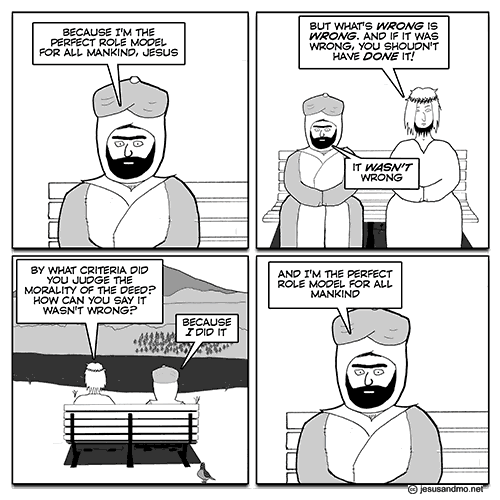

And what about God? Will he/she not intervene to avert catastrophe? No. God has already intervened through the great prophets and teachers, and in person in Jesus, and it hasn’t worked. Well, not enough anyway. Maybe God has always known this, and having done his/her best, is already dreaming a successor to Homo sapiens.

Come on, come on, someone will be saying, all this is some kind of provocation, you don’t really think this. Ah but I do, and one of the strongest supports for my argument is myself: why haven’t I fought harder? Why have I sometimes added my own evil and destructiveness to the common pile? My only excuse is that I’m a human being.

Come on, come on, someone will be saying, all this is some kind of provocation, you don’t really think this. Ah but I do, and one of the strongest supports for my argument is myself: why haven’t I fought harder? Why have I sometimes added my own evil and destructiveness to the common pile? My only excuse is that I’m a human being.

The cross is not the grim story of a psychopathic God who demands satisfaction from his Son, but the sober story of the Son of God who poured out the Father’s generosity in life and death, the victim of moralism, meanness, prejudice, hatred and fear, yet still undefeated. Jesus faithfulness unto death to the generosity of God, is as St Paul recognised, the end of all religious systems designed, like the Torah, to secure the blessing of God. As Jesus knew, the blessing is already given to those who turn to God, in spite of their sins. Now, in that blessing, they have to start again, and again and again.

The cross is not the grim story of a psychopathic God who demands satisfaction from his Son, but the sober story of the Son of God who poured out the Father’s generosity in life and death, the victim of moralism, meanness, prejudice, hatred and fear, yet still undefeated. Jesus faithfulness unto death to the generosity of God, is as St Paul recognised, the end of all religious systems designed, like the Torah, to secure the blessing of God. As Jesus knew, the blessing is already given to those who turn to God, in spite of their sins. Now, in that blessing, they have to start again, and again and again. Writing blogs about matters of faith may create an image in the mind of readers of someone constantly taken up with the great teachings of Christianity, while leading a life of disciplined piety and virtue.

Writing blogs about matters of faith may create an image in the mind of readers of someone constantly taken up with the great teachings of Christianity, while leading a life of disciplined piety and virtue.

Giles Fraser is a priest of the Church of England with an honourable record of putting his own interests at risk for the sake of justice. He writes a weekly column in the Guardian newspaper in which he reflects on political and social issues from a religious perspective. Today his article is a denunciation of Donald Trump, who is certainly a deserving target; but the arguments used in the article are lazy, trite and prejudiced about American Christianity in particular, and Americans in general.

Giles Fraser is a priest of the Church of England with an honourable record of putting his own interests at risk for the sake of justice. He writes a weekly column in the Guardian newspaper in which he reflects on political and social issues from a religious perspective. Today his article is a denunciation of Donald Trump, who is certainly a deserving target; but the arguments used in the article are lazy, trite and prejudiced about American Christianity in particular, and Americans in general.

George Clooney, speaking as a concerned fellow citizen has called Donald Trump a fascist. This may not bother someone who knows as little history as Trump, but it invites Americans to look at the the policies Trump has articulated and to compare them with those of, for example, Mussolini. That’s unfriendly but fair, because it can be examined and found to be true or false. It is part of a debate between fellow citizens.

George Clooney, speaking as a concerned fellow citizen has called Donald Trump a fascist. This may not bother someone who knows as little history as Trump, but it invites Americans to look at the the policies Trump has articulated and to compare them with those of, for example, Mussolini. That’s unfriendly but fair, because it can be examined and found to be true or false. It is part of a debate between fellow citizens.

Dietrich Bonhoeffer, the Greman theologian killed by the Nazis, sketched out the way Christian theology had increasingly found the presence of God where human knowledge was incomplete, such as the origin of the universe, or where human strength gave out, such as in dying. He urged believers rather to find God in the achievements of human knowledge and in the strength of human living. If God was relegated to being a “God of the gaps” he said, then his significance would always diminish as human competence advanced.

Dietrich Bonhoeffer, the Greman theologian killed by the Nazis, sketched out the way Christian theology had increasingly found the presence of God where human knowledge was incomplete, such as the origin of the universe, or where human strength gave out, such as in dying. He urged believers rather to find God in the achievements of human knowledge and in the strength of human living. If God was relegated to being a “God of the gaps” he said, then his significance would always diminish as human competence advanced.

Another ecological necessity we share with other creatures is death: the arrangement of molecules which permits life does not last forever. The fingers that type these words have been around for 74 years today, and have been useful, but already they are neither as agile nor as strong as once they were, and like the brain that articulates these thoughts, they have a term. If biological organisms are programmed to survive, while being made of perishable stuff, reproduction allows the mortal organism to project its life beyond its own death. Indeed, the organism may have done all that it is programmed to do when it has reproduced. Creatures die when they are no longer able to adapt to the changing environment of each new day. Species die when they can no longer adapt to a changing ecosystem, although altered or mutated versions of them may survive, as for example, a smaller sort of cod is proliferating because its human predators want big fish.

Another ecological necessity we share with other creatures is death: the arrangement of molecules which permits life does not last forever. The fingers that type these words have been around for 74 years today, and have been useful, but already they are neither as agile nor as strong as once they were, and like the brain that articulates these thoughts, they have a term. If biological organisms are programmed to survive, while being made of perishable stuff, reproduction allows the mortal organism to project its life beyond its own death. Indeed, the organism may have done all that it is programmed to do when it has reproduced. Creatures die when they are no longer able to adapt to the changing environment of each new day. Species die when they can no longer adapt to a changing ecosystem, although altered or mutated versions of them may survive, as for example, a smaller sort of cod is proliferating because its human predators want big fish.