The Lectionary, a prescribed list of Bible readings for every day of a three year period, used by many Christian denominations, tells me that this coming Sunday I should provide some kind of meditation on the story of Hannah from the first book of Samuel in the Bible. Samuel was a prophet and leader of Israel during the reign of its first king, Saul, and Hannah was his mother.

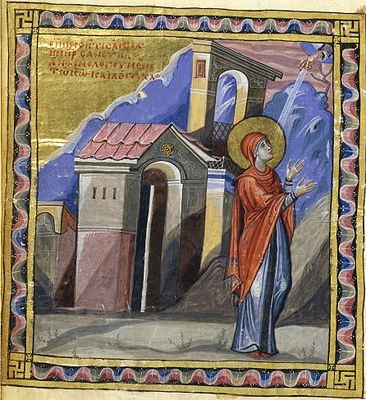

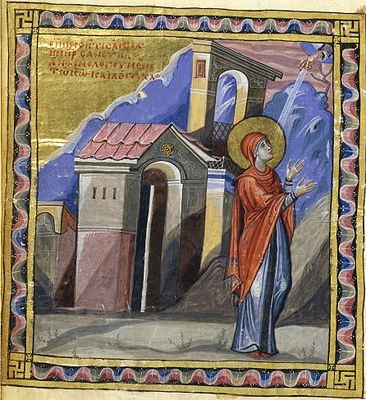

The story of his birth goes like this. Hannah was one of the wives of Elkanah, who loved her in spite of the fact that she remained childless while his other wife had many children. At times Hannah was mocked by the other, making her bitter and determined that she would conceive. She went to the sanctuary and prayed that Yahweh God would give her a child. In fact she promised that if she gave birth to a son she would dedicate him to God, that is to the work of the sanctuary. The presiding Priest Eli seeing her mouth moving with no sound, accused her of being drunk, but when she responded with her story, blessed her and her prayer. She went home, lay with her husband and conceived, giving birth to a son whom she named, Shemuel, or Samuel in English, which she thought was connected with the verb “Sha’al” to ask, as she said, “I asked him from the Lord.”

Subsequently, she takes the weaned child and offers him to the Priest for the service of God. The story also gives her a song of thanksgiving to God which emphasises that God has no respect for human status and often raises up the downtrodden and despised. It was used by the Gospel writer, Luke, as a model for Mary’s song, the Magnificat.

What has this story to say about prayer?

It looks as though Hannah’s prayer is a success. God pays attention to the childless and humiliated wife by giving her the child who is destined to be a leader of Israel. She has gone public with her humiliation by going to the sanctuary to confront God with it. She does not shout aloud, but she prays in the “presence” and tells the Priest what she is doing, so that he adds his weight to her petition.

But she has of course altered her own desire for a child to include her vow that he will be dedicated to God. The reader is meant to feel the weight of this vow and to imagine the wrench of giving over her toddler into the care of the sanctuary. She does not know in advance that the child will be a great leader and that she will be honoured as his mother. She simply offers back to God the child whom God has given to her.

So, good result? Prayer works, especially if what we want can include some kind of bonus for God? But if we believe that God intervenes in worldly events then we might also say that God intervened to make her childless, SO that she would pray to him/ her, and humiliated SO that she might promise her child to the sanctuary, BECAUSE from the start God had destined the child of Elkanah and Hannah to be his/her servant. Behind the dreams and desires of human beings is the dream by which God channels his/her goodness into the world. Something like this view of the overarching imagination of God may have been in the mind of the author of the books of Samuel, who was one of the greatest storytellers ever.

But can I share his sense of God, and in particular should I encourage people with urgent concerns to pray as Hannah did, in the expectation of a positive outcome? Indeed should I myself pray expecting a positive answer, and if I don’t have that expectation, why should I pray at all? The playwrite John Osborne once compared the God of prayers to a hoover “that not only doesn’t beat as it sweeps as it cleans, but actually blows the bloody dust all over the house.” In my work as a clergyman I have known so many situations where people prayed in faith and agony for some good to happen, and it did not. It did not happen. One can say, God has his better purpose. One can ask why mere humans should expect God to arange the universe to suit them. But the truth is it did not happen. It did not happen and the child died. It did not happen and dementia got worse. It did not happen and he did not come back alive from Iraq. It did not happen and they were in Japan when the Tsunami arrived. The good did not happen, but the bad thing did.

And of course, if people have been told to pray, then when it doesn’t work, they sometimes blame themselves. If they had lived better, or had more faith, it would surely have worked. To the shame of the church, sometimes its representatives have defended God by blaming humanity.

An omnipotent God who controls worldly events, sometimes intervening in response to prayer and sometimes refusing to do so, is a powerful but not very likeable invention. Hannah might ultimately disown a God who made her childless so that she would promise her child to his service, just as I would disown a God who allowed Jean Andrew’s girl to die of cancer, but found a parking space for the Baptist minister because he prayed.

I believe in a God in whom we live and move and have our being, who never intervenes, even when Jesus prays for his life to be spared. My invention is of a God who clears a space within the divine being for creation, which continuously takes place through the divine energies, just as a foetus in the womb grows through the energy of the mother. All of creation is continually nourished by God’s creative wisdom. But human beings are given a choice whether to recognise themselves as God’s children, consciously accepting God’s wisdom, or not. When human beings decide to be God’s children, divine goodness flows into the world through them.

When we express our profound desires in prayer to God, we first of all test our wisdom against God’s, our version of what is good against what we know of God’s goodness. This is what Hannah does: she expresses to God the bitterness of her heart. She who has been created by the God of life to bear life has been left barren. He has humiliated and disregarded her. Her prayer has no false piety, but she speaks with passsionate honesty before God. Somewhere in her prayer she meets the divine wisdom, which gives life to all things; and mysteriously her own womanly creativity aligns itself with God’s and she no longer demands but offers herself as God’s partner in goodness, and her child as God’s servant. By expressing her passion to God, she has opened herself to the passion of God.

Now she can go back home with a smile to lie with her husband and conceive. Yes, like many Bible stories, it makes good sense even to readers who have no faith in God. Surely her anxiety and shame about not conceiving are psychological and physiological barriers to conception, and once she has got them out of her heart before God, she is ready to conceive.

The author of Samuel would not have expressed his theology as I have. His way was to work through a succession of subtle stories, involving passionate and sometimes ruthless human beings, to express his profound sense of the involvement of God with his people, God’s desire that they should share divine goodness. These are not simple stories, but had been told and retold by his people over years, gathering new insights, and incorporating new truths. Clumsy, doctrinal interpretations of his work have turned them into mere historical accounts or moral lessons, sapping their energy and hiding their humour.

We can begin to recapture his vision by seeing Hannah as she is: a feisty, angry and passionate woman who tells her soul’s truth to God, and finds herself seduced by God’s desire, to give life to her people through her child.

Yes, yes, you may say, prayer is OK when it does what it did for Hannah, but about Jesus and Jean Andrews? That requires another blog.

1. Have you finished?

1. Have you finished?