I find myself at the present time unexpectedly pushed back into regular ministry to three congregations, with all the joys and stresses that entails. One of the latter is a mistaken reaction from people outside the church to my conduct of public ceremonies like funerals or weddings. They mistake my blunt humour for entertainment, and tell me untruthfully that if their minister was like me they’d come to church. I know they are lying even according to their notions of what coming to church might mean, but my greater concern is with those notions, which imagine Christian faith as a kind of spiritual top-dressing for the lush lawn of their lives. Jesus was brutal towards people who liked his style and insincerely promised to follow him; and doubtless with them in mind, he told his disciples not to “give holy things to dogs or throw pearls to pigs.”

In many decent people these words evoke a sharp intake of breath. Because they are abusive, judgmental and divisive, some might even say, self-righteous, altogether the opposite of what we might expect from Jesus. For that reason, amongst others, I think they are genuinely the words of Jesus and not of his followers. There is a prejudiced edge to them which chimes with Jesus’ initial insult to a Canaanite woman who came asking help for her sick daughter. ( “It would be wrong to take the childrens’ bread and give it to the dogs”) In that case Jesus learned from the woman to reject prejudice. In this case, I think Jesus may just be using a piece of popular wisdom about giving people gifts that they are not capable of appreciating. The great and terrible truths of faith are not for people made unclean by their own relentless superficiality or selfishness. Or rather, they are for them, but they are not ready to receive them to their benefit. They might even seize upon them without changing their lives while claiming to believe them. That is to say, the evangelical announcement of God’s goodness and the call to turn towards it, are always relevant; but the inner realities of worship, prayer, and scripture are only for those who know how precious they are.

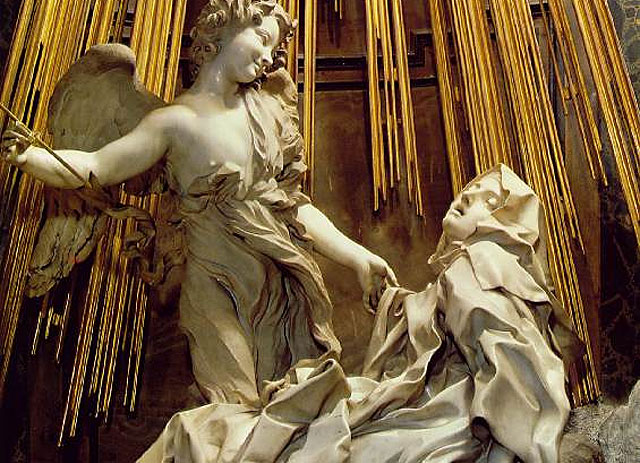

The difficult words also go with Jesus’ command to make no public display of piety, in prayer, or in good deeds. These are only for the eyes of the “Father who sees what is done in secret.” Dietrich Bonhoeffer, the German theologian killed for his opposition to Hitler, spoke of the need for believers to have a secret discipline, communal and personal routines of relating to God, which, like sex, would be private and not for public consumption. The public expression of their faith, he said, should be simply right action.

In these recommendations of Bonhoeffer the tradition of Christian monks and hermits is recovered and renewed. He admired their disciplines of prayer, scripture, poverty and obedience, but not their complete withdrawal from the world. The whole point of the discipline for Bonhoeffer was to equip the believer for faithful action in the world and for the world.

But keen eyes will see I have wandered away from the accusation that Jesus was guilty of abusive lanaguage when he labelled people as dogs or pigs. I concede that the words are pretty robust and might not be approved by a modern bishop or church assembly. But Jesus’ language is often marked by vividness, exaggeration and humour. He wants his followers to see the danger of people who are no better equipped to know the value of holy truths than dogs to appreciate sacrificial leftovers or pigs, pearls.

Many are called, he said, but few are chosen. This saying of Jesus relates to an old Jewish story that God offered his Torah to all nations but only the Jews took it up. In the same way Jesus’ mission invited all to receive God’s goodness, but only a few wanted it. Most people have only scorn for what believers consider as holy or as pearls of wisdom. True religion of any kind is a minority sport.

Mind you, pigs and dogs are my favourite animals.

As I write the day is becoming cloudy, but earlier it was a bright, warm, late-summer day with sunshine, blue sky and scudding clouds. I grabbed my bike and rode by the River Tay, following a good asphalted track from Monifieth to Broughty Ferry and back, stopping frequently to look at things of interest, like the recently created wildflower meadow, with its splendid cornflowers, or the great gathering of swans at the outflow of the Dighty Burn. These birds are often to be found there, along with geese, duck and curlew, as well as numerous small waders.

As I write the day is becoming cloudy, but earlier it was a bright, warm, late-summer day with sunshine, blue sky and scudding clouds. I grabbed my bike and rode by the River Tay, following a good asphalted track from Monifieth to Broughty Ferry and back, stopping frequently to look at things of interest, like the recently created wildflower meadow, with its splendid cornflowers, or the great gathering of swans at the outflow of the Dighty Burn. These birds are often to be found there, along with geese, duck and curlew, as well as numerous small waders. Why do I find it beautiful? I might reckon that someone who didn’t find the drawings of Rembrandt beautiful was entitled to his opinion, but someone who didn’t think swans beautiful I would regard as odd. I don’t think anyone taught me that swans are beautiful, or that there is any evolutionary advantage in swan appreciation, as there might be in my appreciation of a beautiful woman.

Why do I find it beautiful? I might reckon that someone who didn’t find the drawings of Rembrandt beautiful was entitled to his opinion, but someone who didn’t think swans beautiful I would regard as odd. I don’t think anyone taught me that swans are beautiful, or that there is any evolutionary advantage in swan appreciation, as there might be in my appreciation of a beautiful woman.

Of course the author of this remarkable story was a Jew who shared Jewish faith in God. There are many references throughout the story to God, the Lord, but the voice of the One who is beyond all worlds is only heard in one place in the book, namely in Ruth’s declaration quoted above. Yes, it is a human declaration, mentioning lodging, people, gods and death; it is an authentic expression of our passionate dust. And yet it also expresses for its author, the passionate and faithful love of God, promising a loyalty to the beloved that goes all the way to death. In its humanity, this is the word of God, the Beyond in the Midst.

Of course the author of this remarkable story was a Jew who shared Jewish faith in God. There are many references throughout the story to God, the Lord, but the voice of the One who is beyond all worlds is only heard in one place in the book, namely in Ruth’s declaration quoted above. Yes, it is a human declaration, mentioning lodging, people, gods and death; it is an authentic expression of our passionate dust. And yet it also expresses for its author, the passionate and faithful love of God, promising a loyalty to the beloved that goes all the way to death. In its humanity, this is the word of God, the Beyond in the Midst. The morning mail brought me a pleasant surprise in the form of a book I had ordered from a used book supplier in the USA and then forgotten. But here it emerged from its packing, “TImes Alone, Selected Poems of Antonio Machado translated by Robert Bly.” Machado is one of my favourite writers, whom I can just about read in Spanish provided I have a translation nearby when I’m stuck. So this was a pleasure indeed! I have also to admit to a particular additional pleasure that the book is second hand. In this case there is no inscription to give me any glimpse of the original owner, nor any marks in the text to tell me which poems he or she especially enjoyed or was puzzled by. But I do know from the condition of the book that the unknown owner was careful of it and that he/she read it with clean hands. I like to think of this person in the USA somewhere, perhaps with a better knowledge of Spanish than I, reading Machado’s poems, looking through the volume for favourites, as I have already done, pleased at the fact that there are so many that are new. I can fantasise that this original reader, probably now dead -since surely they wouldn’t have given the book away – would have approved of it finding a new life with me. Like all great literature this book will change me as it also changed the life of of its first possessor.

The morning mail brought me a pleasant surprise in the form of a book I had ordered from a used book supplier in the USA and then forgotten. But here it emerged from its packing, “TImes Alone, Selected Poems of Antonio Machado translated by Robert Bly.” Machado is one of my favourite writers, whom I can just about read in Spanish provided I have a translation nearby when I’m stuck. So this was a pleasure indeed! I have also to admit to a particular additional pleasure that the book is second hand. In this case there is no inscription to give me any glimpse of the original owner, nor any marks in the text to tell me which poems he or she especially enjoyed or was puzzled by. But I do know from the condition of the book that the unknown owner was careful of it and that he/she read it with clean hands. I like to think of this person in the USA somewhere, perhaps with a better knowledge of Spanish than I, reading Machado’s poems, looking through the volume for favourites, as I have already done, pleased at the fact that there are so many that are new. I can fantasise that this original reader, probably now dead -since surely they wouldn’t have given the book away – would have approved of it finding a new life with me. Like all great literature this book will change me as it also changed the life of of its first possessor.

I’ve chosen to spend much of my time these days working through the chunk of tradition we call The Bible, in the hope that I can pass on the practice of faithful, critical reading of the Bible to some of my descendants in faith. In an era when the fundamentalist distortion of Christian tradition appeals to those who want to be sure they are right, I want to set an example of how to receive the gift of Scripture as being, like its Lord, divine only in humanity, weakness, fallibility, and unbelievable liveliness. If I can hand on a little of that to a new generation, I’ll be happy.

I’ve chosen to spend much of my time these days working through the chunk of tradition we call The Bible, in the hope that I can pass on the practice of faithful, critical reading of the Bible to some of my descendants in faith. In an era when the fundamentalist distortion of Christian tradition appeals to those who want to be sure they are right, I want to set an example of how to receive the gift of Scripture as being, like its Lord, divine only in humanity, weakness, fallibility, and unbelievable liveliness. If I can hand on a little of that to a new generation, I’ll be happy.