This week my main companions, apart from my family, have been St. Paul and James Kelman. I’ve been reading and translating from Greek Paul’s Letter to The Roman Church, while reading with great pleasure “Dirt Road”, James Kelman’s latest novel.

This week my main companions, apart from my family, have been St. Paul and James Kelman. I’ve been reading and translating from Greek Paul’s Letter to The Roman Church, while reading with great pleasure “Dirt Road”, James Kelman’s latest novel.

One of the things you notice about Paul, when you’re reading his Greek, or even a very literal translation, is his frequent use of the causal connective, “gar” in Greek, “for” in English. Sometimes it’s almost as if he can’t begin a new sentence without this word, which indicates that the previous sentence is not to be left behind by the reader, but taken along in the argument. No circumstance or idea is is simply isolated, but each is connected with what goes before and after. The translator is left trying to vary things by using “therefore,” “with that in mind” , “so then” “because” or simply omitting the connective because often the reader can be relied upon to know that successive sentences are connected.

The reason for this almost obessive insistence on linkage is that for Paul everything in the universe is linked both for good and for ill. Human life is radically open to forces of good and evil: a wrong choice can bind you to evil, whereas as good choice can liberate you from evil and bind you to good. And choice is determined by who you trust. Even a good choice does not totally free you from the grip of competing powers; so Paul will talk about “being rescued” rather than claiming that the rescue is complete. True liberty always lies in the future; this is the hope that gives people the strength to live well. The painful struggle toward new life is characterised by Paul as the pains of childbirth which, in a flash of insight, he claims are shared by the whole universe.

Rescue does not consist of being lifted out of the connectedness of society and the universe, but rather in finding within them a persuasive experience that enables trust in goodness. For Paul, this is the involvement of the source of goodness in the iron chain of connecting events so that goodness itself is subjected to evil and death and is not thereby destroyed but rather born to new life. Those who trust this goodness in its weakness and pain, share in the splendour of its new life, even while they remain part of the connected universe and its evils.

The stylistic feature I most notice in James Kelman’s fine novel is repetition. The story is told from the viewpoint of a seventeen year old boy, whose consciousness of the world is often expressed in overlapping repeated perceptions, each modification re-affirming but also re-defining what has gone before. It is a delicate technique for suggesting how past experience fashions consciousness but is in turn altered by new experience and reflection. For Kelman the individuality of experience, which is important to his view of human heroism, in no way denies the brute determing power of societal and historical circumstance. The hero’s economic status as part of a working class community in Scotland is one such circumstance, the deaths of his sister and mother from a type of cancer for which they had a genetic predisposition, is another.

The sense of particular human lives being subject to predetermined outcomes is as strong in Kelman’s work, as it is in Paul’s theology. Kelman also rejects any notion that the causal chain can simply be snapped, so that people may be free and self-determining. For him, as for Paul, the source of rescue has to be found, if it is found at all, within the painfully determined world, often through a miracle of individual trust, which embraces some available goodness, holds to it, and enables personal dignity and fruitfulness. There is a lot of pain in Kelman’s stories, but he might agree with Paul that it is at least sometimes, like the pain of childbirth: something is being born.

James Kelman would tell me to be very careful about any specious categories that diminish the uniqueness of persons and their pain. The hero of his book is scathing about the religious and social conventions which deny the fact of personal life and death. If there is goodness, it is neither an addition to life nor a philosophy of it, but there, in it, within the predetermined chain of events, a grace arising from it, as the music which the hero loves arises from his culture and his character.

James Kelman would tell me to be very careful about any specious categories that diminish the uniqueness of persons and their pain. The hero of his book is scathing about the religious and social conventions which deny the fact of personal life and death. If there is goodness, it is neither an addition to life nor a philosophy of it, but there, in it, within the predetermined chain of events, a grace arising from it, as the music which the hero loves arises from his culture and his character.

The hard-won nobility of James Kelman’s fiction and its characters, reminds me that a loving attention to particulars is necessary for the creation of beauty. It is also what Paul ascribes to his God.

The Geneva Accords, which govern the treatment of civilians and combatants in war are amongst the noblest documents of humanity, because they push kindness in the direction of justice, as Jesus did, as Moses did, as Mohammed did.

The Geneva Accords, which govern the treatment of civilians and combatants in war are amongst the noblest documents of humanity, because they push kindness in the direction of justice, as Jesus did, as Moses did, as Mohammed did.

Such opposition should be patient, peaceful and popular, encouraging people to see the source of their discontents and to channel their anger into building effective restraints upon its power. In this work, the church would not be alone. The Scottish Green Party in its conference this week, showed a grasp of economic truth and a willingness to devise policies that would limit the destructive powers of capitalism. At least they sounded as if they were living in the same world as me. And there would be other allies also. It’s time the church put its shoulder to the wheel.

Such opposition should be patient, peaceful and popular, encouraging people to see the source of their discontents and to channel their anger into building effective restraints upon its power. In this work, the church would not be alone. The Scottish Green Party in its conference this week, showed a grasp of economic truth and a willingness to devise policies that would limit the destructive powers of capitalism. At least they sounded as if they were living in the same world as me. And there would be other allies also. It’s time the church put its shoulder to the wheel.

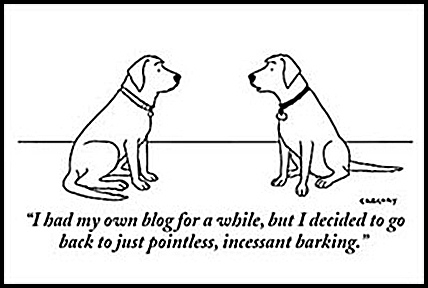

These are not scholarly commentaries. I have of course read many of those and benefitted enormously from them, but my blogs are simply evidence of how I read these writings “under the guidance of the Holy Spirit and within the fellowship of the Church” as my tradition urges me to do. They are closer to what used to be called “devotional reading”, a claim that will arouse derision amongst those who know my impious character.

These are not scholarly commentaries. I have of course read many of those and benefitted enormously from them, but my blogs are simply evidence of how I read these writings “under the guidance of the Holy Spirit and within the fellowship of the Church” as my tradition urges me to do. They are closer to what used to be called “devotional reading”, a claim that will arouse derision amongst those who know my impious character. When I’m tired, as I am for some reason this morning, I choose to read rather than write, and more often than not I read one of the Maigret novels by Simenon, which are being re-issued by Penguin. He is one of the masters of plain storytelling, combining speed of narration with an incomparable skill in inventing the right detail to engage the reader’s imagination. His sentences have an elegant logic, mapping the minutiae of events clearly for the reader to follow. Once he gets you hooked, you stay hooked.

When I’m tired, as I am for some reason this morning, I choose to read rather than write, and more often than not I read one of the Maigret novels by Simenon, which are being re-issued by Penguin. He is one of the masters of plain storytelling, combining speed of narration with an incomparable skill in inventing the right detail to engage the reader’s imagination. His sentences have an elegant logic, mapping the minutiae of events clearly for the reader to follow. Once he gets you hooked, you stay hooked.

“The facts are friendly; God is in the facts….”

“The facts are friendly; God is in the facts….”